With AI (Artificial Intelligence) so prominent these days, it’s easy to feel like the sky…

What Should Go into an Illustration Contract

Having a contract is essential for any illustration assignment. But what should go into that contract can oftentimes be confusing and downright scary, particularly for those of us who are more artistic-minded rather than business-minded. In this post, we’ll take a look at a great resource to help with your contracts and discuss the different things that should go into a standard one and the reasons why.

Every illustration contract is going to be different depending on the industry it’s for. A book publishing contract, for instance, is going to have different needs than an editorial contract or a licensing contract. And contracts that you generate yourself are often going to have different language than contracts supplied to you by the client (and will usually be better for you). The goal of this post is to just discuss the standard boilerplate things an illustrator should be aware of.

So, where do we start? Well, if you’ve never drawn up your own contract or seen one before, there’s a fantastic resource available for under $30. I’m referring, of course, to Tad Crawford’s Business and Legal Forms for Illustrators.

Business and Legal Forms for Illustrators has sample contracts for everything an illustrator might need, as well as a nice explanation of all the terms those contracts use. Forms include things like agency contracts, book publishing contracts, lecture agreements, model release forms, and even a nondisclosure agreement. For those of you out there who still have CD drives, the book even comes with a CD preloaded with all the forms already on it that can easily be put into your own Word doc or InDesign file to tweak to your heart’s content. Quite simply, it’s a resource that every illustrator should own and I encourage everyone to go out and buy it.

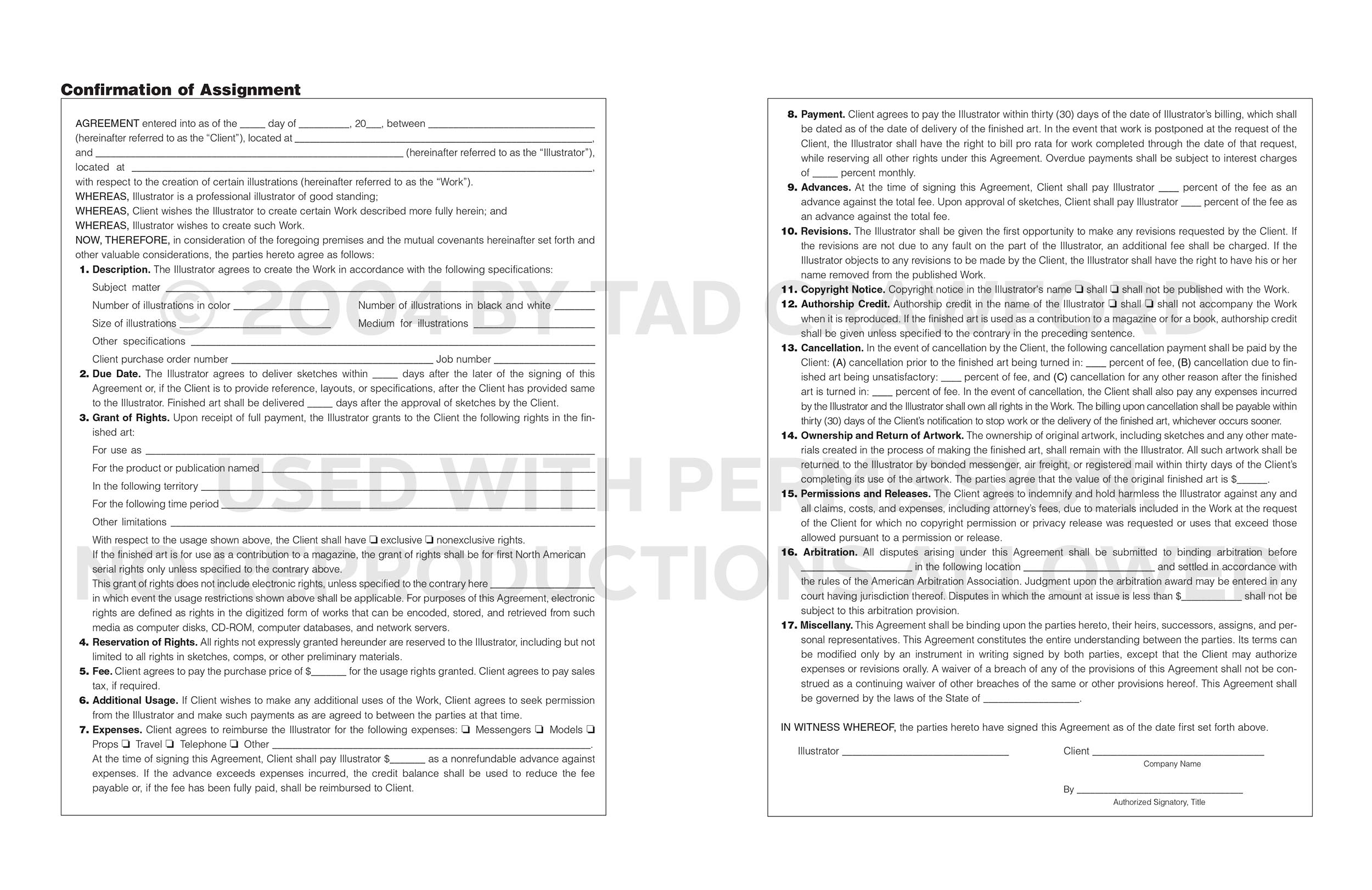

For the purposes of this post, I’m going to refer to Tad’s Confirmation of Assignment form. Mr. Crawford himself was gracious enough to allow me to reproduce it for the educational purposes of this discussion. (And, please note, it’s not for reproduction. If you’d like to use it, please purchase Mr. Crawford’s well-deserving book.) Using this form, I’m going to go through point-by-point to explain what each of these things mean, why they’re important, and suggest some additions and tweaks that I think should be added for a basic, working contract. So let’s examine the form below and try to make sense of it all:

Introduction

Every contract needs an introduction that lists the date the agreement is being entered into, who the different parties are that are agreeing to it, and where they’re located. This form shows a great example of that language.

1. Description

This clause outlines a description of the work that’s being done. This is important because it will cover the full scope of the project. You don’t want to commit to doing twelve illustrations for a certain fee, only to have the client later add three more and expect you to do it for the same price. Having a clear understanding of what the project covers is vital to avoid misunderstandings and ensure the assignment stays within the agreed-upon parameters.

2. Due Date

It’s essential to have due dates clearly written for both sketches and final art, as well as any other important target dates that need to be met. While I agree with the substance of this clause, I do, however, suggest a different way of wording it. In my professional experience, I’ve never had amorphous dates about things being due a certain number of days after a contract is signed. In fact, due to the haste that the business operates in, it’s not uncommon for jobs to have already begun while the finer points of the contract are still being worked out. So I would suggest putting something simpler like:

Sketches will be delivered by _____. Final art will be delivered by _____.

Additionally, I also like to add an extra point here because sometimes art directors sit on your sketches for a long time. What happens if you deliver sketches on a Monday, expecting four days to get to work on the final art that’s due on Friday, but the art direct doesn’t give you approval to go to final until Thursday evening? That could be quite problematic. So I like to add something like this:

In order for the final art due date to be met, sketches must be approved in a reasonable amount of time. If they’re not, a new final art due date must be negotiated or an additional rush fee will be added.

That way it ensures you can do your best work without having to pull an unneeded all-nighter. Or, if you’re still expected to, at least get paid for the hassle.

3. Grant of Rights

As an illustrator, you’re not actually selling art, but the rights of reproduction. It’s in your best interest to limit the client’s rights as much as possible and retain the bulk of them for yourself. A clause indicating what rights are actually being purchased is essential and that’s what this example does. It identifies how the illustration will be used, in what territories (for instance, North America; North America and Canada; English language; World; etc.), the time period (1st printing; 4 months; 10 years; in perpetuity; etc.), and any other limitations on the rights. Additionally it also talks about exclusivity vs. non-exclusivity. As with most illustration-related issues, it’s best to limit exclusivity whenever possible, though most clients will want it while the work exists in the purchased time period so as not to have any conflicts. Electronic rights should also be more money, but these days it’s a hard fight since most clients will also expect to have some kind of web rights or e-device rights. Good luck if you can get extra cash for it, though!

I’d also add something in here about granting of rights only be given if the payment is made in full. That way, if the client fails to pay you, then your legal options are greater because you actually haven’t granted the rights. Something to the effect of:

Any grant of rights is contingent upon payment in full.

4. Reservation of Rights

This is just a simple clause to say that, if it ain’t in the contract, you ain’t giving it away. This contract shows a great example of the kind of language you’d want to use.

5. Fee

This one’s a no-brainer. Even the most basic contracts need to mention the agreed-upon fee. A note about sales tax, though: sales tax applies to goods bought and sold. As an illustrator, you’re selling reproduction rights, not the actual art itself so sales tax is rarely billed. It would only be charged if you were selling that actual art as well as the rights of reproduction.

6. Additional Usage

A standard clause should be added in all contracts to say that the client can only use your work the way it was intended. If they decide to use it for anything else, they need to come back to you and negotiate a new fee for that additional usage.

7. Expenses

Some illustrators have bonafide expenses that may be incurred with the work, outside of just the standard materials. For instance, you may need to pay for model fees if you’re a photorealistic painter, or travel expenses if you’re doing some kind of reportage work, or even font purchases if you’ll be incorporating typography into your work. If you have those kind of costs and the client has agreed to cover them, you’ll want to add a similar clause.

8. Payment

A clause like this is essential because it covers how and when your payment will occur. Standard payments are typically due within 30 days after receiving final art. It’s important to make sure that payment is due upon delivery and never due upon publication. The reason being: what happens if the publication gets delayed? For instance, you’re doing a book cover, but the author get sick and has to postpone the book a year? You could be waiting quite a long time to receive your money then. Or, even worse, the author dies and the book never gets published? Who knows if you’ll ever even get paid if you’ve agreed to an on-publication payment. Additionally, there’s also a point in here about late payments and charging a percentage fee. This is usually 1-2% and accounts for any interest you would have gained if you were able to put that money into a savings account. It’s important because the money rightfully should be yours and insolvent clients will typically try to delay payment so they can earn interest off of it. Something like that sentence guarantees against that happening.

9. Advances

For illustrations where you may get an advance fee, it’s important to have that information in the contract. Advances are particularly helpful if it’s a longterm project and you need cash upfront to keep you afloat while you work on it, or if you’re concerned about the client’s ability to pay, this can be a great assurance to make sure you at least get a good portion of the money should anything catastrophic happen.

10. Revisions

In a contract, it’s vital to ensure that you have the first opportunity to make any revisions to your art. One of the worst feelings is seeing your art published and realizing that the art director did all kinds of horrible things to it without your permission or consultation. Having a clause like this should (theoretically) prevent that.

11. Copyright Notice

Of course, you’ll want to have your copyright notice indicated somewhere near your art and a clause like this guarantees that the client does this. This helps protect you and makes sure no one infringes on your work by saying they didn’t know it was copyrighted.

12. Authorship Credit

Like the copyright notice above, it’s important to be given credit for the work you’ve done. That way, other people will know you were the person who created it and, hopefully, it will lead to more work.

13. Cancellation

Otherwise known as a “kill fee”, a cancellation clause is one of the most important things you can have in a contract. This covers the “what if” variables that come up that may cause a project to be abandoned. In a contract, it’s crucial to state the different percentages that are expected to be paid at different levels of completion should the assignment go belly-up. Usually, for final art that’s been turned in, it’s customary to be paid 100% of the fee, regardless of whether or not the client uses it in the end. Sometimes there may be a smaller percentage if the client is unhappy with the final art, but I’ve never found that to be the case, personally, as most instances of projects being killed arise from far less interesting reasons (a story being delayed because of ground-breaking news, sales and design not seeing eye to eye, etc.). If a job is killed before final art is turned in, I suggest charging anywhere from 33% – 75%, depending on the stage it’s killed. Even if you haven’t begun actual work on the assignment, taking on a job might mean you have to turn down other work in order to clear your schedule for the assignment. If the job gets killed before you start, then that means you’ve lost out on that gig, plus whatever you turned down, so you need to remember that when determining your kill fee. Additionally, as most illustrators will tell you, sketching often takes far more work than the actual final piece, so that’s something else to remember when evaluating that.

14. Ownership and Return of Artwork

Another important clause to have in a contract is one that specifies that the ownership of the artwork you produce remains with you. Remember, when selling an illustration, you’re selling the rights of reproduction, not the art itself. A clause like this also covers what happens in the event that the client damages or destroys your art by accident and specifies its value. The value given should be a realistic value and not some fantasy number.

15. Permissions and Releases

A clause like this is good to have because it ensures you don’t get into any legal hot water based on something the client asked you to use in your art that they said they had permission for, but might not have actually had. For instance, let’s say a client gave you a reference photo to include in your art and told you they had the rights to it, but it turned out they didn’t? You couldn’t be held responsible. In a lot of contracts supplied to you by clients, they’ll have almost identical language but in reverse, claiming they can’t be held responsible for anything you put into your art.

16. Arbitration

You’ll, of course, want a clause in your contracts to cover what happens should things get to a point that the legal system needs to get involved. Depending on your situation and preference, you may want things to go through arbitration or the court system. Different lawyers will have different opinions about that. Additionally, disputes that are worth less than what can be sued for in small claims court typically will not be part of this provision. It’s far easier and cheaper to sue there as you don’t need to involve lawyers or pay exorbitant court costs.

17. Miscellany

The last clause is a standard one that’s included in all contracts that covers which state laws it’s governed by and that anything that’s not in the agreement is not covered by the contract. If something is to be added or changed, it must be done so by a writing instrument (meaning, not verbal), unless it’s small potatoes stuff like revisions or expenses.

Signature

Finally, all contracts end with a space for the parties to sign and date, indicating that they’ve agreed to all the terms set forth above.

Extra things

While the above contract is great, there are a couple of other things I’d also recommend having when drawing up your own:

Tear sheets

I’d suggest putting a clause in here to guarantee that the client gives you a minimum of three tear sheets in the case of printed work. It’s good form for them to do so and looks a lot better than computer printouts in your portfolio.

Number of rounds

I’d also suggest adding a clause limiting the number of rounds for sketches and revisions, or else an additional fee will get added. This prevents certain clients from abusing you by making you do endless changes.

Final thoughts

Contracts can be very scary, but, once you know what actually should go in them, they’re not that bad. If you don’t know legal language, don’t try to use it as certain words may have legal ramifications that you may not be aware of. Instead, just use plain language and strive for clarity. Or, better yet, invest $30 and buy Tad Crawford’s book, Business and Legal Forms for Illustrators, and use that as a starting point for your own contracts.

Speaking of which, a huge thank you to Tad for granting me the right to reproduce his form on this blog for the purposes of our discussion. That was incredibly gracious of him and I (and I’m sure all my readers) am really grateful.

Now that you know what should go into your contracts and where to buy a great resource to help with them, you have no excuse to not work with them anymore!

Hi Neil, this was an excellent read! Thank you for taking the time to post this information. I had one question, that being what are the tear sheets you mentioned? Why 3 tear sheets? Thanks 🙂 Also (quick comment), I really liked the clause about the number of rounds. I’ve been abused by a client in the past and getting the info to prevent that from happening again was great.

Tear sheets are printed samples. So, if it was a book cover, they could send you three jackets (or a full book) or if it was a magazine, 3 copies of the magazine or the page(s) your illustration appeared on. Three is kind of an arbitrary number, but seems like a good amount. It’s enough that you have a few to cut apart or store away for your portfolio.

Glad you like the number of rounds provision! Yep, that happens to all of us eventually, so it’s good to have!

What are the consequences of a publisher who did not fulfill the requirements of a contract agreement, such as, not paying the illustrator by the due date on the contract? I illustrated a book recently, they didn’t pay until 2 weeks after the contracted agreement. The publisher was supposed to compensate me for my illustrations 7 days after the agreement was signed, they didn’t pay until 2 weeks past the due date. In the contract, it said that the agreement was void if I wasn’t compensated within the 7 day period. Also, they did pay me, but as you explained above, make sure it’s not a fantasy number. After doing tons of research, I’ve realised that the pay they offered, And I took was almost unbelievable. $100.00 for 16, 8×10 Chapter sketches. Please send advice.

If the publisher paid you but it was only a little bit late, there really wouldn’t be any consequences. That’s not late enough to warrant anything. You were paid so I don’t think that warrants your contract being nullified. But you should consult an attorney if you’re unsure.

As far as payment, if that’s what you agreed to in the contract, then that’s all they have to pay you. That’s why you need to negotiate before you sign a contract and begin on a job.

Hi, this is a very helpful article, thank you! However, I am a newbie illustrator and one of my first clients asked me something I have not found anywhere. She asked me to not to sell any other illustrations for authors in the UK. I have been reasearching for hours and could not find anything related to the subject.

Excellent article, each clause explained so well! Great job!

Neil,

Thank you for you blog, and this article, this is very interesting.

I am wondering, what if an artist operates under an “artist name”, “aka” type thing, what name should appear in the contract, the name he/she is creating illustration under, or their real name?

Thanks.

So, you’re technically doing business under a DBA. For your contracts, you will need to include your real name. You could write something like, John Doe (doing business as Amazing Illustration Inc.) or something to that effect. Basically, you will need your real name entered into the contract. However, most contracts also list how you should be credited. In that part of the contract, you could then put your DBA name that you’d like to be credited as.

Hello, I have a question:

The publishing company I signed with wants to assign the book’s reproduction rights (with my illustrations) to another Publishing company so they continue printing and selling the book. What kind of clause would be fair for me to sign? In our contract, says they can do so prior me having agreed to this in writing.

This is a complicated question and I would recommend talking this over with a lawyer.

I was reading online articles about freelance illustrator contract making

i believe this (https://www.hellobonsai.com/a/illustration-contract-template) article used yours.

last but not least; the article is informative. Much appreciated

Hi Neil!

I’m just beginning my first illustration commission and would be grateful for any advice and or guidance, if possible, please! The job is for a lady that teaches English to foreign learning disabled youths. She has worked with another artist in the past and already has a small stack of printed booklets made that she uses as a teaching aide for her students. Each booklet is comprised of an original short “story” and 12 colour illustrations, printed on 6 high-quality sheets of q and stapled together down the middle. The compensation is next to nothing but I do want to create the illustrations anyway because I am not working and any income is helpful right now. I know also that if I do a great job it will always lead to something better by the grace of God anyway. So my questions are the following:

1) if I purchase the book you recommended, am I allowed to use the contract as is that Tad created as is … or do I have to create my own original contract and only use his as a guide or example to refer to?

2) do I have to register my art in addition to singing a contract with the client?

1) Yes, you should be able to use his contract via the terms of the book.

2) Yes, you should register your art with the copyright office.